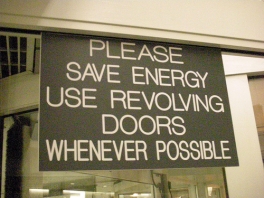

Gamekeepers turned poachers. More revolving doors.

By Elaine Byrne, UNSW

The IMF has observed a recurring trend where senior officials leave regulatory agencies and subsequently take up positions with firms they regulated or supervised. Less than half of all agencies surveyed by the IMF found that the revolving door nature of such appointments has been addressed by the adoption of “cooling-off” periods.

A 2009 OCED report, Revolving Doors, Accountability and Transparency - Emerging Regulatory Concerns and Policy Solutions in the Financial Crisis, went further. In the period between 2000 and 2008, 26 of the 36 members of the UK Financial Services Authority board “had connections at board or senior level with the banking and finance industry either before or after their term or office, whilst nine continued to hold appointments in financial corporations while they were at the FSA.” In the Irish case, from 2003 to 2008, all but three of the thirteen members of Financial Services Regulatory Authority were directors or advisors to the banking and financial services industry.

Public trust in the capability of regulatory agencies collapsed during the financial crisis. The perception of “cosy cartels” between regulators and the regulated was an underlying theme within the banking inquiries in the US, UK, Ireland and Iceland.

As Gregg Fields has already noted on the CLMR portal, this warrants scrutiny from an institutional corruption standpoint. Institutional corruption is defined in terms of trust. This is not about a corruption of individuals but of the institution itself. An influence within an economy of influence may have a certain effect. Although not illegal, the influence has a deviation effect in that it influences the effectiveness of an institution rather than violating existing laws.

The phenomenon of gamekeepers turned poachers potentially creates a labyrinth of interplaying interests which may undermine public trust. For instance, the temptation to use privileged or “insider” knowledge for the benefit of private financial institution at the expense of the regulatory authority, and ultimately the public interest, may exist. Regulatory capture may also be a risk where the decision making process of a public official is influenced not in the public interest but in the possible interest of future employers or clients.

It was in this context that the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON) in the European Parliament proposed amendments last December to the European Commission’s “regulation conferring specific tasks on the European Central Bank concerning policies relating to the prudential supervision of credit institutions.”

Amendment 38 acknowledged that “in order to carry out its supervisory tasks effectively, the ECB should exercise the supervisory tasks conferred on it in full independence, in particular from undue political influence and from industry interference which would affect its operational independence. A cooling-off period shall be introduced for the former members of the Banking Supervisory Board.”

The European Parliament sought to initiate risk management procedures by managing any potential conflicts of interest through the establishment of restrictions on post-office employment in the private sector. This two year mandatory “cooling off” period for members of the Banking Supervisory Board, the body that will oversee the ECB’s supervisory functions, would in theory prevent members from taking paid employment in the private institutions for which the ECB has responsibility for.

This proposed moratorium was complemented by the recommendation to establish a permanent Ethics Committee that will assess if the prospective employment opportunities of ECB supervisory staff amounted to a conflict of interest. It was also recommended that these assessments will be publicly disclosed.

Nonetheless, a majority of member states disagree with the European Parliament. Ongoing negotiations at the current Irish Presidency of the European Council have indicated that these safeguards will not have legislative effect and are now dead.

In April, the Irish financial regulator and Central Bank Deputy Governor announced that he was leaving his position in October, some three years into his five year contract. A clue to Matthew Elderfield’s future intentions was revealed in his brief statement that he is voluntarily and “with immediate effect” stepping back “from involvement in supervisory and other issues if and where a conflict could be perceived.”

Six months of self-regulated gardening leave, rather than the proposed two years outright moratorium, was described in gushing terms as “extraordinary” by the Irish Times. The response to Elderfield’s well-intentioned gesture reveals the low expectations in Irish public life to principled action because of its rare occurrence.

Bloomberg subsequently reported that Elderfield was poised to take up a senior post in compliance at Lloyds Banking Group Plc, Britain’s biggest mortgage lender. Lloyds has a £16.1bn gross loan book in Ireland with 85.5 per cent of the loans impaired or unlikely to be repaid in full. About 25 percent of all Irish mortgages were in arrears at the end of 2012 or have been restructured. The lender, which is 40 per cent owned by the UK government, expressed its firm intent on exiting the Irish market last November when it sold £1.46bn portfolio of distressed Irish property loans to a private equity group for a tenth of their face value.

Elderfield, who also serves as the alternate chairperson of the European Banking Authority, has an intimate knowledge of the Irish market. As the first non-Irishman to head Ireland's regulator, he has led two rounds of stress tests of Ireland’s domestic lenders with another stress test to be held within six months. More than anybody, Elderfield is aware of the full extent of Ireland’s mortgage debt time bomb.

An indication of what’s to come was disclosed in the April ninth review of Ireland. The IMF warned that Ireland's banks remain in a precarious state because mortgage arrears over 90 days were now at 15.8 percent of the total value of mortgages on principal dwellings and 26.9 percent of buy-to-let mortgages by end-2012.

Elderfield’s move to Lloyds is timely for a lender which is so exposed to the Irish market and wishes to quickly leave.

Irish civil servants are barred from taking up private-sector jobs for a year after leaving office unless they have specific government approval. However, executives at the Central Bank and agencies such as National Asset Management Agency (NAMA) and the National Treasury Management Agency (NTMA) are not subject to these restrictions.

Elderfield’s departure is not a unique occurrence on the Irish regulatory scene in recent years. Including Elderfield, six key members of the Central Bank and the NTMA have left in the last twelve months to pursue interests in the private sector.

Michael Torpey, at the Department of Finance banking unit in the NTMA, left in 2013 to become the chief executive of the corporate and treasury division at the Bank of Ireland. The Minister for Finance, Michael Noonan, was questioned in parliament if a conflict of interest then arose given that Torpey headed the shareholder management unit which handled the recent sale by the Government of €1 billion worth of contingent capital notes in Bank of Ireland. The opposition finance spokesperson, Pearse Doherty, described it as “the largest sale of a State asset this year and should be subject to proper scrutiny.”

The Minister however replied that given “a kind of cordon sanitaire for three months” had been applied to Torpey’s appointment; there was “no conflict of interest in the way this was operated.” The government made a commitment when it first came to office in 2011 to introduce two years “gardening leave” for senior public servant in any area of the private sector “involving a potential conflict of interest with their former area of public employment.” This applies however within the context to the introduction of lobbying proposals rather than extending the definition of “public servant” to Central Bank, NAMA or NTMA officials.

Peter Oakes, former director of enforcement at the Central Bank with key responsibilities for issues relating to prudential regulation, conduct of business, consumer protection, securities regulation, and fitness and probity, left in April “take the opportunity to pursue other interests”.

Jonathon McMahon, former director of financial institutions with responsibility for banking supervision, was appointed as a partner and global head of bank restructuring at international accountants Mazars in 2012. He joined the Central Bank in 2010. David Connolly, a specialist in the restructuring and deleveraging unit with the NTMA, resigned in April. It is not yet known what Connolly’s future plans are. Danny Buckley, who had responsibility for Anglo Irish Bank at the NTMA, left to join Bank of Ireland’s group finance department in 2012. Enda Johnson also left the NTMA in 2012 and was subsequently appointed to the role of head of corporate affairs and strategy at the State-controlled AIB.

The Irish affection for revolving doors is shared with her European neighbours, a subject the portal will return to. Despite IMF, OECD and European attention to the phenomena, governments remain reluctant to introduce restrictions. Business as usual.