The Financial System Inquiry and the Importance of Human Systems over Technical Systems

SYDNEY: 19 December 2014 – On 7 December 2014 the Treasurer, The Hon Joe Hockey MP, released the much anticipated final report of the Financial System Inquiry (FSI). When releasing the report Mr Hockey stressed: ‘The Government intends to consult with industry and consumers before making any decisions on the recommendations. This consultation will occur up until 31st March 2015. I look forward to hearing stakeholders’ views on the recommendations over the coming months… Several of the Inquiry’s recommendations, including those on bank capital and the payment system, are for APRA and the RBA to consider as independent regulators. The regulators will consider recommendations relevant to their mandates.’

So, amidst the mass of commentary that has surrounded the release of the FSI final report it is important to remember that at the end of the day it is a report and not government policy, and that the Government may or may not decide to accept all, some, or many of its recommendations. Nevertheless it would be, to paraphrase senior civil servant Sir Humphrey Appleby from the BBC comedy series Yes Minister, a courageous, decision by a Treasurer and/or Commonwealth Government to repudiate a substantial proportion of the recommendations from such a public and extensive inquiry. So, it is likely that many of the FSI’s recommendations will wend their way into government policy. In this regard it is important to remember that the FSI itself was the result of a pledge in September 2013 by then Shadow Treasurer Mr Hockey that if the Coalition did become the next federal Government after the 7 September 2013 election there would be a ‘root and branch inquiry’ into Australia’s financial services sector. Such an inquiry would be the Son of Wallis inquiry, in reference to the highly influential Wallis Inquiry of 1996-1997 which laid out the framework for Australia’s largely successful (in comparison to many overseas counterparts), Twin Peaks approach to financial regulation.

Wallis was open to the development of co-regulatory approaches, particularly in the wholesale sector and a ‘principles based’ approach to financial market regulation. However, Wallis is based on a belief in the strength of market discipline to guide conduct and there is no discussion about the question of culture and what responsibilities market actors should shoulder to safeguard the integrity of the market itself to ensure it realises its fundamental purpose(s). Wallis had an over-reliance on the Efficient Capital Markets Hypothesis and its capacity to deliver allocative efficiencies to society. This emphasis meant that the levers of purpose and culture were not used to the full. Unfortunately, (as discussed in more detail below), history seems set to be repeating itself in relation to the current FSI regarding under-utilisation of these purpose and culture levers.

In his first public speech following the release of the FSI’s final report, chairman Mr David Murray AM re-stated the focus of the FSI and made a number of observations: ‘The Inquiry’s terms of reference required us to examine how Australia’s financial system can be positioned to support economic growth and meet the needs of end users. We were also asked to consider how the system has changed since the Wallis Inquiry, including the effects of the Global Financial Crisis…. While many of the Wallis Inquiry recommendations have stood the test of time, there are two areas where this Inquiry has formed a different view.’

The two areas which Mr Murray described as ‘paradigm shifts’ since the Wallis Inquiry relate to resilience and consumer outcomes. Regarding the resilience issue Mr Murray described how amongst its total forty four recommendations the FSI had recommended ‘practical steps to reduce moral hazard’ in areas such as: capital ratios of Australian banks; a leverage ratio; narrowing the gaps regarding mortgage risk weightings between the various providers; a framework for loss absorption and recapitalisation to be developed by the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA); and prohibiting direct borrowing by superannuation funds. Regarding consumer outcomes the FSI identified three problems with current arrangements: firms not taking enough responsibility for treating consumers fairly; too much reliance on disclosure and financial literacy; and the need for regulatory agencies to be more proactive. Consequently the FSI had recommended: ‘the introduction of a targeted and principles-based product design and distribution obligation’; an industry funding model for the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) which would provide additional resources to be more proactive and a raft of changes in the area of superannuation to increase competition and better meet the needs of individual Australians.

The overall effects of these recommendations if they become government policy are likely to be largely positive. They are handed down by an inquiry which had two general themes: ‘funding the Australian economy and competition’, thereby emphasising three core objectives: ‘efficiency, resilience and fairness’. In turn these led to the five specific themes of the report to: strengthen the economy by making the financial system more resilient; lift the value of the superannuation system and retirement incomes; drive economic growth and productivity through settings that promote innovation; enhance confidence and trust by creating an environment in which financial firms treat customers fairly; and enhance regulator independence and accountability, and minimise the need for future regulation.

However, as international law firm Allens notes: ‘Besides superannuation, there are no specific recommendations about governance – although there is lots of discussion about the need to improve culture in financial institutions and that it is the leaders and their own conduct that will determine organisational culture. There is also nothing on vertical integration – the suggestion is that with improved culture and obligations to act in the interests of customers, vertical integration won't pose the mis-selling risk it might otherwise do.’ Perhaps the FSI is overly optimistic about the inherent capacities (and desire?) of financial organisations and those within them to operate business models that prioritise the interests of consumers without sustained regulatory pressure. ASIC is certainly aware that such problems are deep-rooted within elements of the financial services sector, in the words of deputy chair Mr Peter Kell: ‘Unfortunately we see problems in a range of (financial planning) firms and we’ve seen them over some time… This is an industry that has to lift its game, this is an industry that has to put customers back at the centre of their business models.’

Unsurprisingly, these problems are not confined to Australia, or indeed to financial planning units within financial organisations, as evidenced in November 2014 by Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England and Chair of the Financial Stability Board (FSB), who is clearly angered and frustrated by a litany of financial benchmark manipulation scandals in the UK and other jurisdictions: ‘Fundamental change is needed to institutional culture, to compensation arrangements and to markets….the succession of scandals mean it is simply untenable now to argue that the problem is one of a few bad apples. The issue is with the barrels in which they are stored. Leaders and senior managers must be personally responsible for setting the cultural norms of their institutions. But in some parts of the financial sector the link between seniority and accountability had become blurred and, in some cases, severed. The public were rightly angered that so many of the leaders and senior managers who were responsible for sowing the seeds of the crisis and for allowing cultures to develop in which gross misconduct took place have walked away from their actions or inactions.’

The FSI was an opportunity to recommend specific pathways to increase obligations and accountability standards within financial organisations to mandate improved standards of behaviour, for example through licensing processes. It is an opportunity that has not been grasped, and as such, with my colleague Justin O’Brien, I fall into the category of disappointed submitters to the FSI process: ‘The Inquiry recognises it has not addressed all issues put before it by interested parties.’ In our 28 November 2013 submission to the FSI on its draft Terms of Reference we:’…strongly recommend to the inquiry that it examines how operational cultural norms within the financial services sector determine the levels of integrity, manageable risk and accountability that may be achieved in capital markets.’ And in our 31 March 2014 submission prior to the FSI’s Interim Report: ‘Recommendation Four: In line with the UK, assess the precise nature of culture and its impact on competition and advance concrete mechanisms to hold stated commitments to account, thus enhancing accountability.’ And ‘Recommendation Seven: Place verifiable conduct at the heart of the Inquiry’s response to changed financial conditions to be informed by legislative change.’

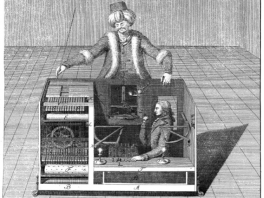

It is especially disappointing that the FSI has not been more proactive regarding governance in its recommendations, because in several of his speeches during the course of the FSI, Mr Murray acknowledged how crucial it is to focus on human systems in regulatory environments and how they are decisive in terms of behaviour and effect. For example in Sydney in November 2014, in his last public speech before the release of the final report Mr Murray stated: ‘We put in an enormous effort every day to make sure machines — which don’t have an opinion — are working properly. But we spend far less time on human systems, which affect people. Human systems are actually far more important than technical systems.’ It is unclear how significant the FSI recommendations will be in directly influencing human systems in financial regulation in Australia to protect better the interests of Australian citizens, all of whom are consumers of financial services. Given the realities of contemporary federal parliamentary mathematics in Canberra, especially in the Senate, it may well be parliamentary mechanisms such as the current Parliamentary Joint Committee on Corporations and Financial Services Inquiry into proposals to lift the professional, ethical and education standards in the financial services industry, that can prioritise the issue of how human agency systems can be regulated to improve operational cultures in the Australian financial system. As 2015 proceeds the Treasurer and the Commonwealth Government will decide how many of the FSI’s forty four recommendations they will adopt, the consultation window until 31 March 2015 also affords an opportunity to raise further the profile of how human agency systems shape financial regulation and practice.

Add new comment